Abraham Lincoln and the Meaning of Independence Day

When we think of the Fourth of July, we often think of backyard barbecues with friends, baseball, and maybe a beer or two. This year, with COVID-19, maybe we can at least have the beer. But Independence Day was originally more than just a party, and the Fourth ought to be something more to us. It commemorates the signing of the Declaration of Independence, our first national statement of beliefs. We need to consider this year, perhaps more than most, if we still believe in its principles:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

The Founding Fathers meant something specific by these words, and they really believed the Declaration was true. Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers that to say something is self-evident means that if you understand the language, and have a properly functioning mind, you must assent to it. That is what the Founders meant when they said it was self-evident that all men are created equal with certain rights. They meant that for all time, and in all places, men are equal.

But it is not clear that we still believe this. Some think that rights are different in different cultures, or perhaps in different times. Others think the Founders were a bunch of frauds—hypocrites because, after all, when they signed the Declaration, slavery existed and many of the Founders owned slaves. On this particular point, our modern critics of the founding would find themselves—unintentionally and unwillingly, of course—in a strange partnership with pro-slavery southern secessionists before the Civil War who argued that the Declaration was just a bunch of “glittering generalities” that were obviously untrue, or that they had only ever been intended to apply to white men, because only white men were equal and free in 1776.

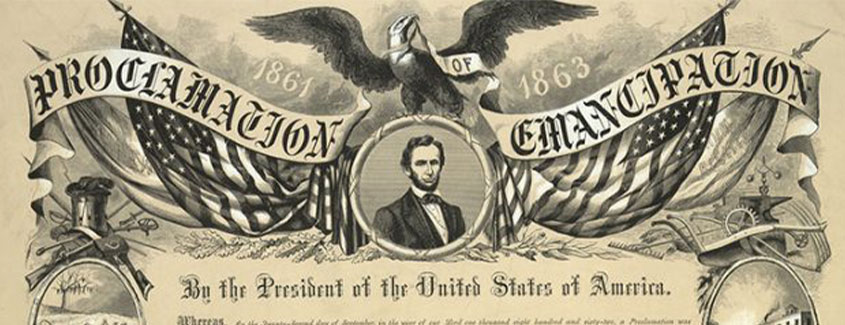

Abraham Lincoln disagreed. He claimed that this interpretation misunderstood both the Founders themselves and the purpose of the Declaration. Lincoln argued that most of the Founders opposed slavery and worked to eliminate it. They wrote the Declaration of Independence, they passed the Northwest Territory Ordinance, forbidding the extension of slavery into the territory north and west of the Ohio River, and they passed legislation in 1807, to take effect in 1808, to end the slave trade, the very first year allowed under the Constitution.

Lincoln also pushed back against the notion that a principle can be proven false simply on the basis that its supporters are hypocrites. It is true, obviously, that some Founders owned slaves, and some, like Jefferson, never freed them. But that does not negate their principles. We are all hypocrites about something. Where is the man or woman who always lives up to his or her principles?

Lincoln claimed that the fact that all men were not legally equal and free at the time of the Declaration did not falsify it because, after all, the United States was also not independent at the time the Declaration of Independence was written. The Declaration was not declaring what was but what ought to be: it declared political, philosophical, and even theological principles. It was an argument that because all men are created equal, and endowed by their Creator with the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, that the colonies ought to be independent, and that all men, and indeed all women, ought to be free. It created a principle that the country would forever strive to reach. Lincoln believed the heart of America is not a race, a language, a geography, or even the Constitution—it is the principles enshrined in the Declaration.

The question today, much as in Lincoln’s time, is whether we as a people still believe the Declaration is true. And if it is not true, what, other than economic and political power, both of which look rather doubtful these days, really holds us together as a people? We have a choice to make: We can abandon any pretense of believing in shared principles, and conclude that our shared democratic life is really just about power, or we can conclude that there are certain principles that we all ought to believe, because they are True, even if we have not yet figured out how to fully put them into practice. And then, just maybe, we can work on improving some of our practices to bring them more into line with our principles.

That would be worth celebrating over a beer or two in the backyard.